Dis — Intro

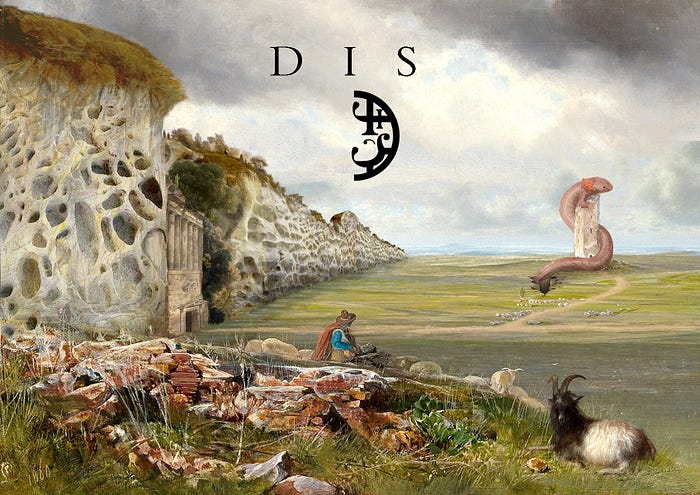

Dis is a place of hidden things. The whole principality is enclosed in stone, with towering cliffs on three sides and a gigantic wall running along its northern border, shielding the land from sight and invaders.

The Great Wall is one of the gifts of Saint Mammon, the archdevil patron and founder of Dis, the golden lord master of roads and chains. The wall is made of Living Stone, a bone-like substance hard as concrete, the same the devil used to lay out the first road network of the empire. There are many hints that the living stone died at some point: centuries have passed since the last time the wall grew or repaired itself. All other Mammon creations are now simple rock. No one in Dis will admit to it: the stone is just sleeping.

Dite, the capital city of Dis, is famous for its walls with circles and circles of mural defenses that divide the various districts. The buildings’ architecture is typically organized around central courtyards, with small windows and few openings on the outside. The city may appear lush with vegetation from far away, but walking the streets you will meet only stone: the gardens are all kept in the cloisters, carefully tended but never shared.

Dite perches on a secure hill overlooking the surroundings, afraid to expand beyond it. But it still grows vertically: towers sprung as reeds from the urban marsh and every construction have deep and intricated underground levels, with rooms, cellars, and storerooms.

Such a dense city has always had problems with public hygiene and developed the most sophisticated and vast sewer and plumbing system.

You can see why Dis, and Dite in particular, have fame as the cradle of architects and engineers.

Such a dense and crowded capital city is in stark contrast with the rest of the nation. Dis is mostly empty: endless and wavy plains crisscrossed by dry walls delimiting the pastures. Occasionally, there will be outlook towers, isolated castles, and lonely abbeys. Towns have walls in some way or another, sometimes just with massive and crude rock fences.

The land is a cheap karst, good enough to sustain decent agriculture but impossible to develop in fruitful plantations. Therefore, most of the territory is used for herding. Wool is one of the main products along with cheeses and parchments.

The real riches are underground.

Dis consists almost entirely of the Tartarus Peninsula, a shard of the Beyond, a piece of hell. Tartarus was a prison for the damned, an endless dungeon where sinners were kept as punishment, especially the ones considered dangerous: the giants were jailed there after their revolt, as well as rebel divinities and mortals who gained illicit powers.

The piece of Tartarus ended in the material world retains some extraordinary features: as a way to prevent the escape from hell, the Tartarus had complex space foldings that are retained on a small scale. Therefore, the labyrinthine caves, full of underground rivers, ample grottos, and bottomless chasms, are not disorienting only because they are intricate but also because they move. Only a few fixed paths in the underground exist, most of the tunnel will shift and turn in time, becoming dead ends or leading somewhere unseen. It’s a slow process that causes only minor tremors most of the time, but on other occasions, sinkholes and crevasses can form, creating gaps where the creatures from below can exit on the surface.

The Tartarus peninsula has its peculiar “mana environment” with different concentrations of different kinds of mana. Pockets of high concentrations of green mana, linked to life and vitality, allow for otherwise inefficient metabolisms and feeding strategies. Chemosynthetic lichens and lithophagic bacteria are the basis of a complex underground ecosystem where fungi, arthropods, and oozes have a pivotal role, but also host mammals and birds, both mutated to live in the lightless tunnels.

Sometimes, wonders and monstrosities emerge from the depth: albino wurms have attacked shepherds’ towns, entire flocks have been devoured by land sharks, and fields have been razed by crystal crabs. These rare apparitions hint at bigger and more complex ecosystems and are a draw for many scholars and adventurers to explore the belly of the dungeons.

Curiosity is a strong motivator, but profit works even better: Tartarus’ flora and fauna offer chances for gain: the exotic and peculiar materials one can harvest have many uses, even as food.

But the real opportunities come from prospecting since many ores of gold and silver hide in the tunnels. Before the collapse was customary to wear something gold or silver, a gift to the entities that shepherd the soul to the afterlife. Those metals were not particularly precious but had a symbolic meaning and a magical application, allowing the psychopomp birds to easily found the recently departed. Now all those precious metals amount to an incalculable wealth.

The Disite aristocracy is probably the richest of all the empire, controlling most of the gold extraction, goldsmithing, and banking. They are generous patrons, filling their windowless villas with art and antiquities, but they are very selective about who to show them.